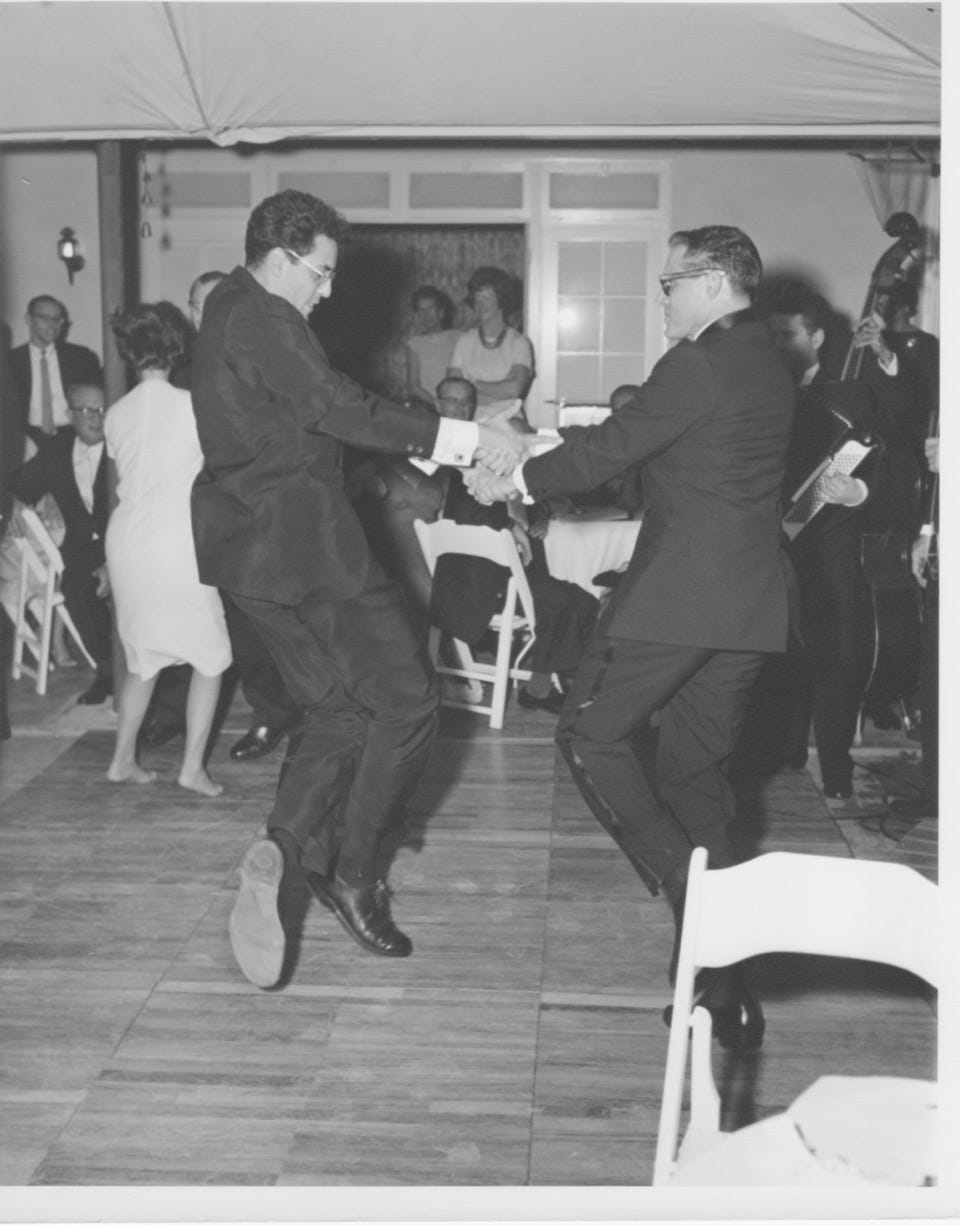

Photo: Victor and my father dancing at the wedding of my parents.

Back yard of my grandparents’ home at 701 North Rexford, Beverly Hills. 1964

Wait! Didn’t Raf just use the photo above, and the story about Victor just a week or so ago? Yes, I did. I wrote it and said to our Kehilla (Minyan Ohr Chadash): Hey, I can deliver the Dvar on Shabbat! But, of course, someone had been scheduled some time earlier. Then the member scheduled to give the dvar for Vayishlach cancelled. I was asked to fill in. I reused the story of Victor.

Tada!

>>>

In this parsha:

At the very end of Vayeitzei, last week, Jacob encountered angels and called the place Mahanaim. From there, in this week's parsha, he sent angels ahead to Esau his brother (who was on the edge of fratricide a couple of weeks ago). The angels report that Esau is approaching. With an army.

The army fills Jacob with fear beyond fratricide. He seems to forsee his clan massacred and wealth plundered. He divides the clan and estate into two camps, so at least some of his extended family and assets can survive. He prays for salvation. He sends gifts to Esau. Not roses or chocolate. Not greeting cards. He sends legal tender: Hundreds of goats. Hundreds of ewes. Dozens of camels, dozens of cows. They are sent not in one package. But in installments. Think "gift of the hour" for a whole day.

The wives and children are sent off, separate from the asset-camps.

An angel (Esau's guardian angel, says Rashi) wrestles with Jacob and renames him Israel.

Jacob sees Esau-and-army approaching. He splits his children into three groups with their mothers and sends one group at a time ahead to Esau, and himself approaches Esau last. The brothers hug and weep. Esau refuses the many gifts of Jacob. After fighting over the check (as it were), Esau accepts. Esau and Jacob go their separate ways. Jacob sets up an altar and proclaims G-d of Israel.

Jacob's daughter Dina is raped by a local prince. The prince demands that his father negotiate with Jacob so he may keep Dina as a wife. Jacob's sons are outraged by the incident. The local king, Hamor, proposes that Jacob's clan intermarry with the locals. Hamor's son, the rapist, offers to pay any bride price. (At this point, is it a bride price or a peace price?) The sons of Jacob suggest that intermarriage is possible, but only if the local men are circumsised. Hamor and his son convince their people to circumsise themselves, with an overt pitch that the wealth of Jacob's family will be distributed among them via intermarriage.

When the local men are in pain from the recent circumsision, Dinah's brothers go through the city and kill all the men. They take Dinah home and plunder the city.

Jacob is upset with the violence. He fears that his small tribe is vulnerable to the local clans should they ally themselves against the tribe of Jacob.

G-d solves the dilemma by advising Jacob to relocate to a new area in Beth El.

G-d reaffirms the earlier name change to Israel and renews the promise of the land and of the future nation that will arise from Jacob's family. Benjamin, the last of the twelve heads of the tribes, is born to Rachel who dies in childbirth. Isaac dies at 180 years of age. Esau and Jacob reunite to bury him.

Esau leaves the area. His progeny are detailed, including Amalek and other future enemies of Israel.

<<<

Thus begins the saga of the 12 sons of Jacob. The future friction among the brothers seems like an inheritance. Their grandfather Laban deceived Jacob by putting the wrong daughter under the wedding veil. Years later, Rachel steals Laban's idols (payback?). Before any of the sons are born the two sister-wives are jealous of each other, having one upped the other (Rachel was chosen by Jacob, but Leah gets the scoop of becoming the senior spouse). This morphs into raw competition between sisters Leah and Rachel over providing sons for the family, which reaches its conclusion this week with Rachel's death in childbirth.

And now, as Esau approaches Jacob's camp, there is fear of fratricide and worse.

Maternal jealousy and inter-uncle hatred will flow, in subsequent parshiot, to the spaces between the 12 brothers.

These hard feelings will ultimately, in future parshiot, drive the brothers to the brink of fratricide.

But this parsha and its predecessors are also filled with agreements of peace. In earlier parshiot kings make peace with Avraham. Last week Laban and Jacob came to terms. This week bloodshed is averted by Jacob's peace-payments.

I can't help but notice that in Vayishlach and earlier parshiot, peace is bought and not wished for. No kumbaya camp fires. No rituals with a shaman's drum. No poems of love. Peace is bought and paid in legal tender. In Lech Lecha the Pharoth buys peace with Avraham for an enormous sum. Ditto with Avimelech in Vaiera. This week Jacob pays what looks like millions of dollars to achieve peace with Esau.

Let's think about this for a moment.

There is a principle in the Torah:

"עַ֚יִן תַּ֣חַת עַ֔יִן שֵׁ֖ן תַּ֣חַת שֵׁ֑ן יָ֚ד תַּ֣חַת יָ֔ד רֶ֖גֶל תַּ֥חַת רָֽגֶל"

-- An eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth, a hand for a hand, a foot for a foot.

This principle is stated with slightly different wording in sefers Shemot, Dvarim and Vayikra. Three times at least. Yet every Jew knows that we implement this principle figuratively, not literaly. In practice peace (which is synonym for justice) is achieved not via poking out an eye but by compensating the value of the eye. With legal tender, be that dollars or donkeys.

I imagine that this concept comes easily to us. And without distaste.

However the situation in this parsha is different. Jacob uses money to overcome ill will. Ill will that Jacob himself created by deceiving Isaac and outmanauvering Esau for birthight and blessing.

You could potentially say the same thing about Avraham's manauvering with the Pharoh and Avimelch. Avraham, were he standing here today, might say, "I had to migrate because of famine or politics, and found myself subject to lascivious local leaders. I had to lie about my relationship with Sarah to avoid being targeted for death." But the ultimate reality is that a relational breach was created and it was solved with a large payout to Avraham in the coin of the realm (be that cash, camel or cow).

Two questions: First, why is money used to repair emotional and relational breaches? And second, why does that make us uncomfortable?

Allow me to suggest that we ascribe attributes to wealth, some constructive and some not. Essentially it is something of value. Something we keep close. Giving of it is in some way giving of ourselves.

But why should that make us uncomfortable? Jacob bribes his way to survival, and then the brothers hug and maintain a constructive relationship. Is our discomfort from the image of immediate family using money to achieve domestic peace?

Allow me to suggest the stigma about buying peace with money is a European or Christian concept that we may have internalized. We know that using money to buy peace and solve interpersonal conflict has a long history within the Jewish world and also in non-Jewish cultures of the Middle East. It is commonly done in cases of manslaughter, murder, and other injustices. Our discomfort with using money to buy peace within a family is, perhaps, from the European culture we breathe.

These payouts are done post-rupture. What of making peace by avoiding or mitigating the conflict to begin with?

Later in the Torah, peacemakers of this kind will also be found among the brothers. But at this juncture we note that seeds of peace are there alongside jealousy, guilt and envy. Each parsha, it seems, has both deception and reconciliation. (Not always over the same matter or by the same people.)

This inter-parsha thread offers a meta lesson: In every era and situation, people of peace work from bare beginnings to keep us from falling completely off the rails.

This week's parsha begins in a place called Mahanaim, named at the end of Veyetze. We understand Mahanaim to be located just to the east of the Jordan river, between the Sea of Galilee and the Dead Sea. (E.g. to the south of Tiberias.)

There is another Mahanaim

There is another Mahanaim, 30 miles or so north of Tiberias. It is on route 90, the road to Metula, the northernmost tip of Israel. When I read Mahanaim in the parsha, I thought "I have hitch hiked from there several times."

Ahh, the cars and pickups I flagged were not at the Mahanaim of the Parsha. But for over 50 years, waving a car down there led to a man of peace.

One of the photos on my screen saver is my father and his best friend, Victor Friedman, dancing a Greek dance at the wedding of my parents in 1964. My mother always told me they danced for hours that night. Israeli and Greek dances. (In the back yard of my grandmother's house that was just sold in 2020.)

Victor lived until his death on Kibbutz Gadot. Until Israel Rail was built out in the North, the way you got to Gadot was to take a bus to Tiberias, and then get on the bus to Metula. Getting on that bus, ask for Mahanaim. At Mahanaim you hitch hike the last 5 or 10 miles to Gadot.

I last did this with our sons about five years ago. (Now there is a bus that goes from the nearest rail station to the Gadot entrance.)

Wait. The parsha is about Jacob and the beginning of Israel, not bus routes.

The parshiot show, over and over, how deception, jealousy and conflict lead to defensiveness and sometimes trauma. Undoing such damage takes work. (The monuments and altars built by Jacob and others are both memorials to peace-agreements and perhaps a kind of physical therapy to let go of the angst?)

Victor, though he lived near Mahanaim-North for decades, did not build stone monuments. Rather, he went to a nearby Bedouin village several times a week.

To coach girls basketball.

For girls, activities in Bedouin and Arab towns are limited. Victor knew that basketball is a big personal development tool for Israeli youth. So he brought it first to a girls team at the Tuba-Zangariyye high school. And then the middle school. And then to girls so small they just drop the basketball into a bucket on the ground.

In this town of 6,000 a few miles from Gadot, Victor built a humane monument.

And in my household, over a few decades, the phone would ring every few years on a weekday night. A voice would say "It's Victor, I'm here." No advance notice. No awareness on our part that he was coming to the states. He was just here. And I'd go pick him up at whatever train or bus station he was at and he'd come over for dinner. And then I'd take him back to a train or bus station and send him on his way.

Victor was my father's closest friend. I often refer to him as an uncle. He played a far larger role in my life than any of my actual uncles. He was a kibbutznik who always had a kippah in his pocket when he travelled around the States.

He died in 2018. Our daughter Alma and I were at his funeral.

We turned right at "Mahanaim North" to get there.

A mukhtar from Tuba-Zangaria spoke. And reminded everyone that avoiding hurt, offense and trauma takes work. And that Victor built a huge bridge between the villages and brought, year after year, a great gift to the girls of Tuba-Zangaria.

Making peace by avoiding rupture takes work.

---

Photo: Victor and my father dancing at the wedding of my parents. Back yard of 701 North Rexford, Beverly Hills. 1964

---

Wildpeace - Yehuda Amichai

Not the peace of a cease-fire,

not even the vision of the wolf and the lamb,

but rather

as in the heart when the excitement is over

and you can talk only about a great weariness.

I know that I know how to kill,

that makes me an adult.

And my son plays with a toy gun that knows

how to open and close its eyes and say Mama.

A peace

without the big noise of beating swords into ploughshares,

without words, without

the thud of the heavy rubber stamp: let it be

light, floating, like lazy white foam.

A little rest for the wounds—

who speaks of healing?

(And the howl of the orphans is passed from one generation

to the next, as in a relay race:

the baton never falls.)

Let it come

like wildflowers,

suddenly, because the field

must have it: wildpeace.

// It was difficult to find a Hebrew version that would allow the text to be copied .

http://www.teachgreatjewishbooks.org/resource-kits/yehuda-amichais-wildpeace#resources

--end--